Cooperation and Teamwork

The Cooperation and Teamwork workshop usually takes up two whole blocks, meaning one full day at the ten-day Basic Training in Peacebuilding organised by CNA. That is why the workshop example below consists of two parts and takes a total of some seven hours to implement.

The aims of workshops on this topic mainly concern trying out decision-making by consensus, analysing and practising communication, better understanding of teamwork and its implications, mapping elements of quality teamwork, re-examining one’s own behaviour when working and when working in a team, creating space for receiving and giving feedback, as well as getting to know each other and developing the group.

Workshop Example (Part One)

Good morning

Game

Brainstorming: What Is Teamwork?

Duration: 10 minutes

Jigsaw Puzzle*

Type of exercise: Interactive, experiential exercise

Duration: 30–40 minutes

Materials: 3–4 sets of envelopes containing pieces of the jigsaw puzzle (see instructions on the next page)

Exercise description

The participants split into groups of five (the remaining participants can be observers). Everyone stays in the same room, but the groups sit in separate circles. It would be best if they can sit on the floor. A set of five envelopes marked with numbers 1 through 5 is prepared for each group. The envelopes contain pieces to make up a square. Each member of the group receives an envelope. The instructions say that they are not to open the envelopes before they are told to do so. Slowly read the instructions at least twice, making sure everyone has heard them.

Instructions:

“Each person has received an envelope with pieces that form a square. At my signal, the group should start the task of putting together five squares of equal size. The task is complete when every member of the group has a completed square in front of them.”

Make sure everyone understands the task. Then read the rules given below. It would be best to have the rules written out in large letters and displayed prominently.

Rules:

“No talking or communicating of any kind is allowed during the exercise. You may not take pieces from other members of the group.

Pieces may only be given to the person to your right or placed in the middle of the circle. You may take pieces placed in the middle of the circle.”

Evaluation of the exercise is conducted after all groups have completed the task.

Exercise evaluation

Suggested questions to evaluate the exercise: What was it like?

Did you follow the rules? What did you do?

Some of you had only one piece of the puzzle. Did anyone notice this? How did such people feel?

What was it like and what did you do when someone was keeping part of the puzzle and not seeing the solution?

How did you feel when you put together your square only to realise you had to take it apart in order to give away a piece?

What did the observers notice?

What was it like cooperating without verbal communication?

* Izvor: Karl Heinz Bittl-Drempetic. Gewaltfrei Handeln: Ein Handbuch für die Trainingsarbeit (Nürnberg: City Verlag, 1996), str. 329–331.

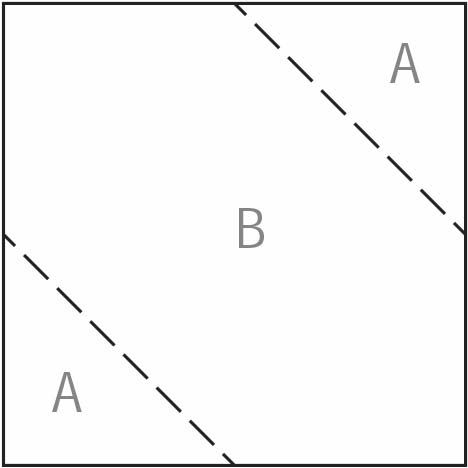

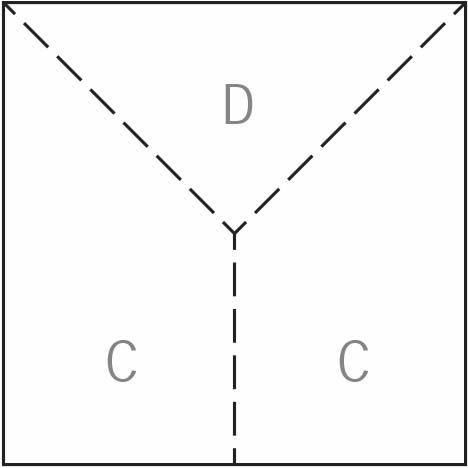

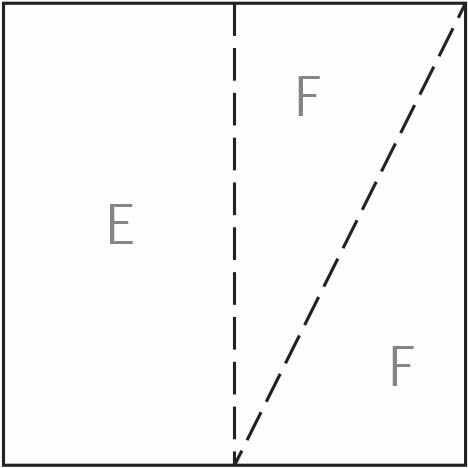

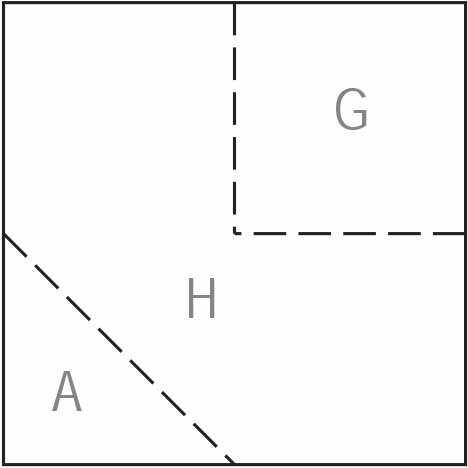

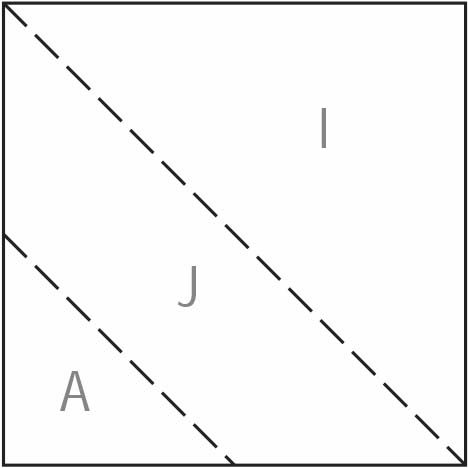

Materials for the Jigsaw Puzzle exercise

For one set of envelopes you will need five square-shaped pieces of paper of the same size (you can cut an A4 paper to get squares of 21 x 21 cm). Cut each square into parts as shown on the diagram below to get the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle. The pieces of the puzzle are assigned letters.

Then put the pieces into separate envelopes as follows:

Into Envelope 1 pack one piece marked with each of the letters A, C, H and I;

Envelope 2 – A, A, A and E;

Envelope 3 – J;

Envelope 4 – D and F;

Envelope 5 – B, C, F and G.

Repeat these steps three more times to make four more sets of envelopes. It is recommended to make each set with different coloured paper. This helps avoid mixing the pieces betwee the groups and makes it easier to collect the pieces after the exercise to be used again.

Note

There is only one way to put together all five squares. It is possible to put together one square, but this makes it impossible to put together the remaining four. It often happens that one person quickly manages to put together their square and then waits for the rest of the group to finish, only to realise after a while, usually due to the frustration of the other group members, that they must take apart their square because it contains a piece needed to put together another square. The task is difficult, but not too difficult. Sometimes all it takes is time for the group members to realise they must cooperate in order to complete the task. We haven’t yet had a situation where a group was unable to complete their squares. The exercise may cause frustration, impatience, neglecting others, competition within the group, and especially competition with other groups (over who will be the first to complete the task), as well as complete disregard for the rules of the exercise, all of which provides very useful material for analysing teamwork and cooperation. When behaviour during cooperation is criticised, care should be taken that the criticism isn’t judgemental or personal, and participants should be reminded that the aim was not to compete but to learn about cooperation. This type of intervention is important to prevent someone retreating under criticism or feeling like they’re being “punished for their mistakes”, especially because self-criticism and criticism are indispensable for in-depth work during the training and due attention should be given from the very beginning to practising a culture of critique.

Voting on a Verdict

Type of exercise: Role play

Duration: 60–90 minutes

Materials: Two charts of voting outcomes (see annex), a lot of small notes of equal size to serve as ballots, two flipchart papers to record the voting results

Exercise description

The participants are split into two groups of seven people and they work in separate spaces. Two or three people are observers in each group (depending on the total number of participants). Slowly and clearly read the story about the context for the exercise, at least twice.

Story:

“You are two rival humanitarian organisations working with children. Both your organisations currently work on multiple important projects planned for the upcoming two years (one of the main projects is procurement of aids for children with disabilities). One officer from each of the two organisations has been arrested for using the privileges given to humanitarian organisations for personal gain (evasion of customs taxes). Importing technical equipment was at issue. All the other employees (all of you) knew about this but turned a blind eye. The public prosecutor suspects that the two officers cooperated in these illegal activities.

You are faced with the question: Is your organisation guilty as a whole?

The group votes by secret ballot and the decision is made by simple majority vote.”

The two groups then go work in separate spaces. It is important that they are in different room so that they cannot overhear each other.

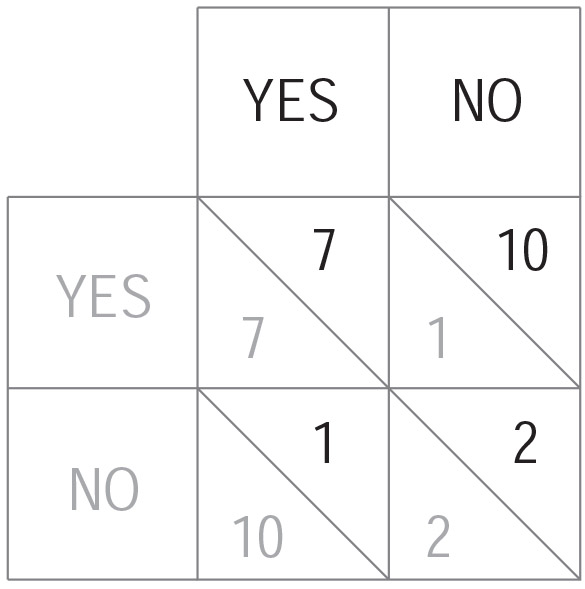

It is explained to each group that the outcome of the vote on whether they are guilty as an organisation will have different outcomes and give each group a copy of the table that illustrates this:

Possible voting outcomes

- If both organisations admit their guilt, they will be banned from working for 7 months.

- If both organisations deny their guilt, they will be banned from working for two months.

- If one organisation admits to being guilty, but the other does not, the organisation that admitted its guilt will be banned from working for one month, and the organisation that did not will be banned from working for 10 months.

You can download the voting outcomes chart

Voting plan:

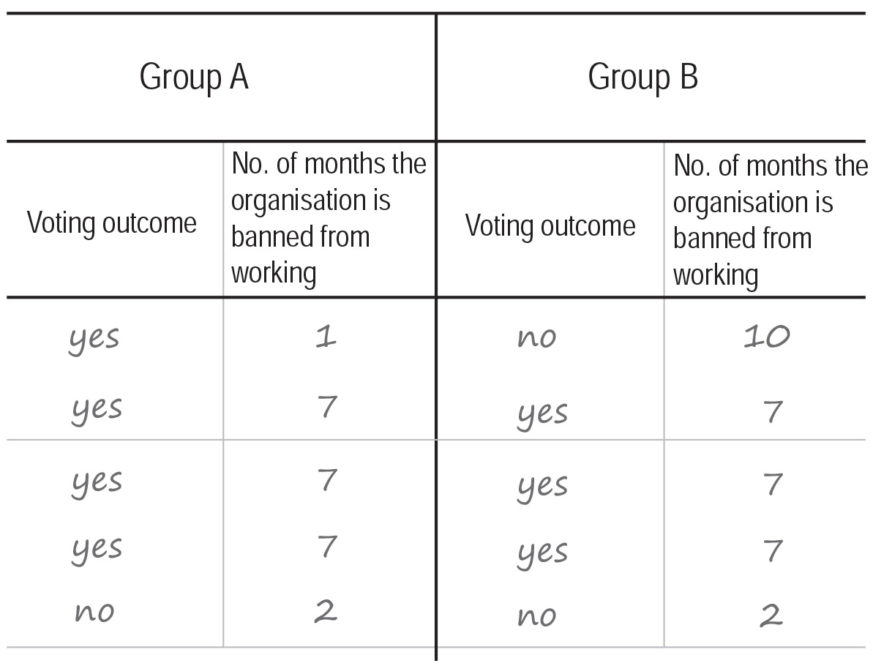

1st round: Everyone receives a ballot paper to enter their vote (“Guilty” or “Not Guilty”). Everyone votes individually, without consultations within the group. The trainer delivers the verdict based on the results of the vote on both groups (to each group) and the corresponding punishment, as well as specifically how the other group voted. She writes this on the chart on the flipchart paper.

Example chart for recording the votes:

Each group receives a copy of the chart.

2nd round: Voting takes place again without prior consultation and the results are given to both groups. Only then does each group get five minutes to confer and nominate a negotiator to go negotiate with the other group. After negotiations, they again have a short time (two minutes or so) to confer within the group and then they vote. The trainer again delivers the verdict based on the results of the vote of both groups (to each group) and the corresponding punishment, as well as specifically how the other group voted. If from this point the voting results remain the same three times in a row and the same sanction is pronounced, whatever the ration of votes, the exercise ends.

If the exercise does not end by the fifth round of voting, the trainer announces that the next round will be the last. The negotiators should have a chance to meet again, and a short time to confer within the groups, followed by the final round of voting and the end of the exercise.

Some people may decline to vote during the exercise, which can lead to the vote being tied. If the results of the vote within the group are tied, the following rule is applied: the result will be determined in relation to the previous vote by making the tied vote opposite to the previous vote (if the results of the previous vote were “Not Guilty” then the result of the tied vote will be “Guilty” and vice versa).

Exercise evaluation

Suggested questions to evaluate the exercise:

How did you vote? How satisfied are you with the result? How satisfied are you with the process?

What did the observers notice?

Note

Implementing this exercise may be complicated due to the sequencing of steps. It is recommended that you lead the exercise only after you’ve had the opportunity to assist a trainer with experience in implementing this exercise. Those who do decide to use this exercise usually find that it becomes indispensable for discussing teamwork, cooperation, leadership and communication because of the material it offers. The participants find it fairly easy to take on their roles, because the story is close enough to real life and not unfamiliar. Because moral dilemmas appear at various levels, it is almost impossible for the process and for consultations within the groups, and especially negotiations with the other group to go smoothly. This also provides ample material for analysing teamwork and communication. However, often the moral dilemmas are sidelined and competition with the other group takes centre stage. In a brief time, this exercise gives us a snapshot of how peer pressure functions, how we communicate with others when we have polarised opinions, how easily we overlook people on our team, how we take the path of least resistance or how we are defiant, the image we create of the other group, etc. The exercise can elicit strong emotional reactions, primarily of frustration, so the evaluation should be conducted carefully and skilfully in order for people to emerge from it with a feeling that it was worth getting upset because they learned so much. It is very important that the evaluation does not leave the impression that one group was morally superior to the other and that insights into displayed weaknesses leave enough room to hearing out, understanding and accepting criticism.

Cutting Paper

Type of exercise: Interactive, experiential exercise

Duration: 45 minutes

Materials: Large paper and scissors

Exercise description

Call for volunteers who want to participate in the exercise, a total of seven people. Their task is to first think of a paper shape they would each like to make for themselves. Then they receive a large paper, one pair of scissors and the following instructions: in the size and shape they imagined, but without leaving any leftover paper in the end.”

The rest of the group observes the process. Communication is allowed. Time: 20 minutes.

Evaluation

Suggested questions to evaluate the exercise:

How satisfied are you with the result (the paper shape you cut out)? Did you cut out the shape you initially envisaged?

How satisfied are you with the process? Were there different roles in the process and what were they like? How did you agree on how you would complete the task? How did you decide about who would begin and who would finish the cutting?

What did the observers notice?

How do the elements of this exercise relate to your daily lives?

Note

The number of volunteers for this exercise may vary and need not be exactly 7 (it may be 5 or 11). It is important that the number is not easily divisible so that people are not tempted to take the path of least resistance and simply divide the paper into equal rectangles, which is what the group will often decide to do once they hear what the task is.

The exercise may sound very simple, but it can simulate various phases in teamwork: agreement on joint work, the way that the group will reach agreement and make a decision, the process of decision-making about how to cut up the paper, and the final implementation of their decision. Most often the first stage, which can be decisive for teamwork, is completely skipped over and the group goes straight to suggestions about how to divide the paper or even straight to implementation without any prior agreement. This leads to neglecting the process and the focus shifts to completing the task any which way, with any kind of result. However, just like in real life, dissatisfaction with the result is directly correlated to dissatisfaction with the process and with having no influence over the outcome. We may blame others for this – e.g. those who took on a more proactive role – or we may end up blaming ourselves for not expressing our dissatisfaction on time and constructively influencing the cooperation process.

If the group is already exhausted from interaction and challenges (if the previous exercises were fraught), it may be best to leave this exercise for another time. It would be a shame to “waste” it in a situation of low energy and motivation, when people are susceptible to taking the path of least resistance, because in that case we would not receive the kind of material for analysis that this exercise can offer. In that case it is better to have the participants work in small groups, discussing their observations about teamwork.